August 10, 2010 Firenze

Our class visit in Florence began with a trip to the top of Brunelleschi’s life work, the dome atop the Florence Cathedral. Neil and I caught a bus with NJIT critics Dan Kopec and Darius Sollohub leaving Siena at 6:50 to arrive in Florence at 8:10. Access to the cupola opened at 8:30.

Two major reasons to climb the dome: you can see Brunelleschi’s dome-within-a-dome construction techniques, which is similar to that of the dome on St. Peter’s (Michelangelo modeled its design after Brunelleschi’s dome), but the structure is more exposed in Brunelleschi’s, which architecture minds like ourselves tend to enjoy. Reason number two is, of course, to enjoy the scenic Florentine panorama.

Our route through Florence was strikingly similar to the route we took during our fly-through at the beginning of our epic weekend (I guess our route really was the most direct way to see all the big sights in the city) but we spent a little less time drooling over the Duomo and more time at spots that fewer tourists know how to visit.

We spent a little bit of sketching time at Santa Maria Novella this time:

A new stop along the way was the Laurentian Library, a private book collection and reading room of the Medici, for which Michelangelo designed the grand entry stair hall.

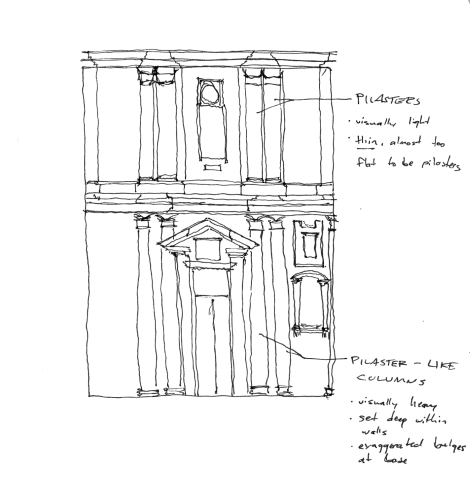

Although it is extremely subtle, probably even unnoticed to the visitor uneducated in architectural history, the genius behind the room’s design is in the proportions of the ornamental classical forms on and in the walls. How deep can a column be set into a wall before it reads like a pilaster? And how thin can a pilaster get before it is no longer a pilaster and just part of the wall? Michelangelo pushes these parameters far beyond the proportional limits that came with Classicism. Distorted proportions are also evident In the room’s oversized decorative scrolls, keystones, and a slightly awkward stair riser-to-tread ratio on the stair itself.

Plan sketch -- the outer stairs did not have railings on the outside. Interesting choice, Michelangelo.

My assessment of the space Michelangelo is my homeboy, so it’s always a good time standing in one of his spaces or being in the presence of one of his works. I remembered when we looked at the Laurentian Library in history of architecture that the play with proportions was intended to create a visually heavy aesthetic that forcefully imply a slower pace of travel between the Library’s entrance in the San Lorenzo cathedral cloister and the reading room itself, but to be honest, I didn’t read it that way. If anything, I would agree that the proportions’ heavy aesthetic do create a minor sense of discomfort, even a subtle claustrophobia. But for the architecture student, it was neat to see the same architectural elements repeated one above the other—the windows, pediments, columns and pilasters are repeated on both the ground and upper levels of the space—but with change in level came change in proportion. The ground level elements were bulkier, heavier, and had a solid girth to them, while the upper level elements were visually lighter and almost merely wall treatment instead of their own entities. The lightness on the upper level seemed to make the space seem taller, and made me want to ascend the stairs to get away from the heaviness surrounding me on the ground level; in a sense I was being seduced into climbing up the stairs into the reading room…Good call, Michelangelo.

Along the way we also saw an early Brunelleschi design, the Cappella Pazzi, part of Santa Croce cathedral. We were intrigued that Brunelleschi didn’t know how to get a pilaster to turn the corner…

Highlight number two of the day was after our large group dispersed; now I was walking around Florence with Neil, Brad, and Adam L. The last leg of our smaller-group wanderings led us across the Arno River to the Michelangelo Piazza (offering a great panoramic view of Florence), Palazzo Pitti (the private residence of the good old Medici family who economically fueled most of the Renaissance work that left me breathless countless number of times during this study abroad experience), and my personal favorite, another church whose design Brunelleschi had a hand in, Santo Spirito. This façade sparked a heated debate between Neil, Adam, and myself:

Neil and Adam hated this thing. Notice in the photo that Adam is pointing backward him at the strikingly bare basilica entrance wall—and he’s not using his pointer finger.

Their argument was that the church, probably built during the Renaissance or the Baroque, was plain for its time. Unornamented. Where was all the white marble? The sculptures? The stained glass and the spires? There’s nothing to look at! How can people possibly approach this door and be inspired to worship a God?

While I see where they are coming from, I find great beauty in its simplicity. As awesome as St. Peter’s and the Duomos of Florence, Siena, and Milan are, the detail of their craftwork seeks to overwhelm worshippers and visitors.

Taking a look for a moment at Alberti’s design for the façade of Santa Maria Novella, also in Florence—Alberti spent most of his architectural career trying to find a “pure” way to decorate the basilica shape using forms from Classicism. The problem is essentially one of graphic design; how should the shape that already exists architecturally be decorated using Classical, ideal proportions? S.M. Novella is one of his latest, most developed attempts at this endeavor, where he explores the possibility of using the shape of an ancient Greek temple front as a doorstep to the church (the Greek temple form is also utilized in Basilica di Sant’Andrea, which some historians will argue is the ultimate successful answer to the problem, so Alberti, good call to you too).

Rather than trying to be some ideal masterpiece of Classical perfection, this church smoothes over the graphic design problem and just tries to be what it is, a church, not a canvas. The architecture exists without the help of over-the-top decoration. It is an amazingly 20th century modern solution to a 14th century problem.

And if I must go on, compare this façade to that of San Lorenzo.

San Lorenzo has no façade. And in fact, neither did the Florentine Duomo, until Florence became the capital city in 1865, when the city received a face-lift to suit its new political status. The façade of this church wasn’t ignored at all; it was finished with plaster. This façade was more designed than most churches of its time.

After standing outside and arguing over the building, we called it quits and, over some gelato during the walk back to the bus to Siena, we agreed to disagree.

- Leave a comment

- Posted under SIENA

Leave a comment